My Visit to the Putri Cempo Landfill: Learning About Waste-to-Energy in Indonesia.

Visiting the Putri Cempo Final Disposal Site (TPA) was the first time I saw various facilities and equipment used in waste management—some I was already familiar with, and others were entirely new to me.

Not many people may realize it, but the waste we produce doesn’t just cause pollution and take up land—it also generates greenhouse gas emissions. As of now, it’s estimated that 514 landfills across Indonesia’s cities and regencies will produce 58.22 million tons of CO₂ equivalent emissions by 2030 (Bappenas, 2023). Because of this, local governments are trying to manage and process waste that still has value or can be useful before sending it to the final disposal site (TPA). Waste-to-energy (WTE) solutions are also needed to create sustainable energy sources by converting methane into biogas or electricity (Kumari & Raghubanshi, 2023), or by producing Refuse-Derived Fuel (RDF).

I learned a lot while visiting the TPSTs (Temporary Waste Processing Sites) in Sleman, Pasuruhan Magelang, Modalan, and Putri Cempo in Solo. Most TPSTs process their waste into RDF—an alternative fuel product. For example, TPST Sendangsari in Sleman, Yogyakarta, processes 40 tons of waste per day into RDF. However, one common issue across these sites is the limited processing capacity and the unpleasant odor that still reaches nearby residential areas, despite the use of blowers.

Meanwhile, the Pasuruhan TPST can process up to 100 tons of waste per day into RDF. The TPST in Modalan, Bantul Regency, processes about 50 tons per day. In addition to producing RDF, Modalan TPST also recycles plastic waste and uses incineration technology. A key challenge here is the high volume of organic and residual waste, which means much of it ends up being incinerated.

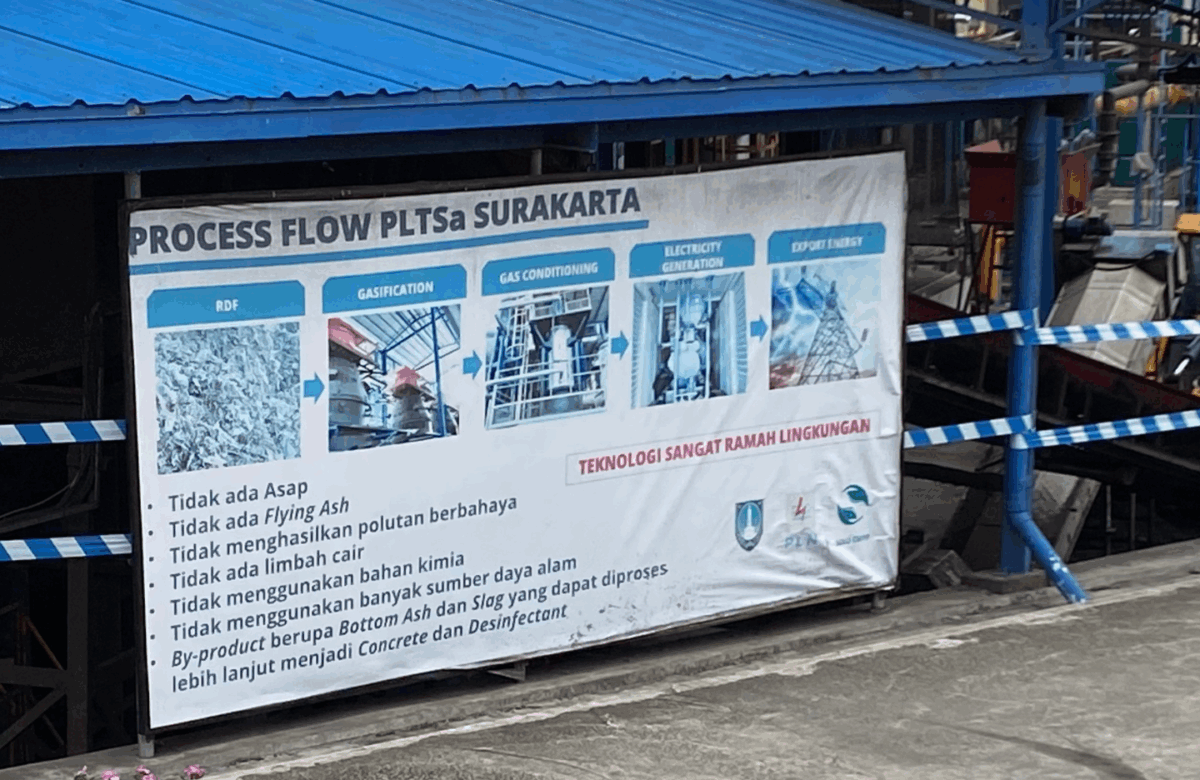

What caught my special attention was the Putri Cempo site, which stands out among the locations I visited—it already converts waste into electricity. Located in Surakarta, Central Java, TPA Putri Cempo has been operating for about 32 years. It features a Waste-to-Energy power plant (PLTSa) (pic on left) consisting of 8 gasifiers, which have been running since 2023. However, only two gasifier units operate 24/7; the rest are not run simultaneously.

My interest in waste-to-energy efforts stems from my undergraduate research, where I explored how to produce biogas from waste to be used for cooking in a pesantren (Islamic boarding school). Turning waste into energy is also important to help prevent methane emissions from escaping into the atmosphere—a major contributor to greenhouse gases. Why is this critical? Because 39.23% of waste in Indonesia is organic (SIPSN, 2024), which makes proper management and treatment essential.

Interestingly, Putri Cempo also processes waste into RDF, which is then used in the gasification process. The facility has advanced infrastructure for handling waste, particularly in terms of gasification technology.

Unfortunately, during my visit, the gasification process was temporarily halted for maintenance. I had hoped to learn more about the technology, especially since the PLTSa hasn’t yet generated financial profit, although operations continue as usual. In terms of emissions, the gasification process at Putri Cempo needs to be closely monitored. Since the waste is burned at specific temperatures, it requires further treatment to ensure the emissions are safe for the environment. Besides electricity, the process also produces biochar, which can be used as fertilizer.

Considering the potential and quality of the waste produced, there is a clear opportunity to develop renewable energy from waste using current and evolving technologies. According to Presidential Regulation No. 35 of 2018 on Accelerating the Development of Environmentally Friendly Waste-to-Energy Power Plants, the Indonesian government has committed to building PLTSa facilities in 12 cities across the country. Waste management requires support not only from the government but also from the public and private sectors (Lasaiba, 2024).

Pic. End product of bio-char on the floor.

Going forward, I would actually recommend reducing reliance on waste-to-energy (WTE) processing. That’s because this method still produces N₂O and CO₂ emissions—although lower than open dumping systems or illegal burning. The best way forward is for the public to reduce and separate their waste at the source. Communities can also play a role by composting organic waste and recycling inorganic materials. At the TPST or TPA level, waste can be sorted using material recovery facilities. These approaches can result in lower greenhouse gas emissions than WTE methods (Chen & Lo, 2016).

Reference:

Bappenas. (2023). Analisis Potensi Off-taker Refuse Derived Fuel (RDF) 2023.

Chen, Y.-C., & Lo, S.-L. (2016). Evaluation of greenhouse gas emissions for several municipal solid waste management strategies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 113, 606–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.11.058

Kumari, T., & Raghubanshi, A. S. (2023). Waste management practices in the developing nations: challenges and opportunities. In Waste Management and Resource Recycling in the Developing World (pp. 773–797). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-90463-6.00017-8

Lasaiba, M. a. (2024). Strategi Inovatif untuk Pengelolaan Sampah Perkotaan: Integrasi Teknologi dan Partisipasi Masyarakat. Journal Geografi Dan Pendidikan Geografi.